Exactly five years ago I moved from the network creative agency world to a pretty different one – to Jellyfish, an independent global marketing company uniting media, creative and data with AI.

Sorry if this isn’t your bag – I’m fully aware that announcements about job moves and anniversaries tend to be full of humble braggadocio, and that the weird LinkedIn invention of the ‘work anniversary’ really shouldn’t be a thing.

However, a blog post I wrote about my move in early 2021 (‘I’ve never heard of Jellyfish’) got a surprising amount of interest from creative agency people who were surprised by the move, as Jellyfish was a lot less well-known to people in the creative and brand world back then than the agencies I’d come from (although Jellyfish was and still is better known in the search and media worlds), so for anyone that was interested in that, this is a follow-up.

The main thing people would say to me back then was ‘who are Jellyfish?’, hence the original blog’s title and key visual, a play on the famous Economist poster (‘“I’ve never read The Economist”, Management trainee, aged 42’). https://thetomroach.com/2021/03/25/ive-never-heard-of-jellyfish/

Five years on, many more people have now heard of Jellyfish and pure awareness is less of a problem, although the brand is at different stages of development in different markets globally, and when people ask me questions about Jellyfish now, it’s less ‘who are they?’ and more ‘what exactly do you guys do?’. So the brand challenge for us has shifted from being mostly about improving awareness to more about improving familiarity and consideration. We’ve apparently had some success at something I’ve blogged hard about not fully believing in: driving people down the funnel.

Hence a visual I’ve made with Gemini for this blog, also a play on a great Economist poster although a lesser known one (‘Somebody mentions Jordan. You think of a Middle Eastern country with a 3.3% growth rate’) from a distant time when Jordan, the alter ego of UK glamour model Katie Price, was a permanent fixture in the tabloids.

Anyway, on my fifth work anniversary I thought I’d try to find a way to summarise what’s been going on at Jellyfish over this time from my admittedly totally biased and brand and creative-oriented POV.

Jellyfish five years on

When I joined in 2021, Jellyfish was in the midst of a transition from its origins as a performance marketing agency into a global, integrated full-service digital agency. It was already by then a global company with around 2000 people in c40 offices around the world, offering a range of digital marketing services, spanning SEO, paid media, martech, creative, content, social, production, localization, and training.

Jellyfish’s founder Rob Pierre had shown remarkable vision in taking a local IT consultancy in Reigate and transforming it into a cutting edge global marketing company, via amongst other things, strong partnerships with the platforms, especially Google, and a strong eye for strategic acquisitions.

By 2020 he and the leadership had recognised the growth limitations of focusing on the bottom of the funnel, and were growing by heading up it. In fact the thing that first brought me to their attention was an article by me about the combined benefits of brand & performance, ‘The Wrong and The Short Of It’ (https://thetomroach.com/2024/06/15/the-wrong-and-the-short-of-it-again/) that had got shared around the company. That article got me a new job. Thank you so much, James Parker, for the opportunity. (Content marketing and personal branding works, people).

For a summary of what I got up to in my first 12 months at Jellyfish, from 2021-2022, read this: (https://thetomroach.com/2022/02/23/12-months-since-moving-to-jellyfish-heres-what-ive-been-up-to/)

2023: enter The Brandtech Group

Jellyfish’s acquisition by The Brandtech Group in 2023 is the most significant single event to happen over this time and it’s changed some things but not others.

Strategist and sage Tom Morton posted a comment on LinkedIn that Brandtech’s brace of three major acquisitions (Oliver, Jellyfish and Pencil) covered the three most strategically important developments in marketing services. Oliver for inhousing; Jellyfish for brand and performance; Pencil for GenAI creative and content.

“We should look at Jellyfish as one of the great bets of today’s creative economy. The Brandtech Group saw three mega trends – marketing as brand and performance, inhousing, and generative AI – and backed smart, human-friendly companies in each space”.

I’m hugely biased but have to agree.

For another glowing assessment of Brandtech, try this from independent consultant Justin Billingsley who puts it in the Goldilocks zone – not too hot, and burning up like the big holdcos, and not too cold, small and unscalable like the boutiques:

“Brandtech sits at a $4B valuation with 7,000 employees, $1B revenue, and portfolio companies that span the full marketing technology stack. Not too hot. Not too cold. Just right.”

https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/brandtech-goldilocks-company-justin-billingsley-rvhqe/

Put probably too simply, Brandtech essentially offers clients three ways for marketers to access Pencil’s AI/agentic core – via self-service, inhouse, or a serviced model. But crucially not via 100,000 people across 200 offices and a complex cornucopia of networks and agency names.

Take a look at Pencil and enterprise version Pencil Pro here: https://trypencil.com/

Creative at Jellyfish

Creative at Jellyfish takes many forms, and is more diverse and tech-driven than my experience of working in creative agencies. Our creative business comprises 400+ people, around 20% of Jellyfish by headcount but significantly more in terms of revenue. We’re making everything from integrated full-funnel campaigns for major brands like Toyota, running social for Apple TV, making AI-driven assets and adapting and localising them for Google products and services, social content for Netflix show launches, global AI-made integrated campaigns for Uber, and performance and ecommerce assets for many of our media accounts.

You can see from just those brand names what an unbelievable client list we have – it’s one that any agency would kill for. Progressive, ambitious brands, many of whom are themselves global platforms. And unlike creative or media agencies, we do a phenomenal range of connected things for them. Often a relationship starts in a single area and then over time grows organically to include a diverse range of services. Different markets and offices have slightly different centres of gravity, but our creatives are one tight collective wherever their office may be in the world.

I wrote about how creatives will be at the heart of the AI revolution last year (https://www.marketingweek.com/tom-roach-creative-marketing-ai/) and this was inspired by seeing how our creative people are embracing AI technology in their work, specifically Pencil Pro, that sits at the heart of all of our creative processes. Our creative teams are embracing and getting the most from AI faster than other companies – because we have the technology, because it’s an expectation that’s being driven from the very top, and because of the nature of our client relationships. Many of our client relationships start with more of a performance media or production perspective, and as they’re very often themselves tech platforms they’re also faster to embrace technology and the way we work.

We’re seeing first hand how AI technology accelerates convergence in a host of different ways – across creative and media, across production and creative origination, and across job roles to name just a few.

A major development in my time here has been Jellyfish hiring its first Global ECD, Jo Wallace. She arrived from Monks in December 2023 and what a difference she’s made. On joining she immediately led the winning pitch for Apple TV, and within 18 months we’d picked up our first ever Cannes Lion for the social campaign the wider creative team created to launch S2 of Apple TV’s landmark show, Severance. We’ve since won more than 40 creative awards for a range of clients, including 2x Grand Clios for Apple TV and Netflix.

Her work championing AI as an essential tool in every creative’s armoury is being felt really strongly. She leads from the front, hosting AI-based events, writing thought-pieces and running regular creative sessions where she sets her teams briefs and exercises to help them evolve their skills for the new era we’re now all in. My advice to any agency hiring an ECD today is – get one who rolls her sleeves up, writes her own prompts and inspires and trains her teams to do the same.

Share of model

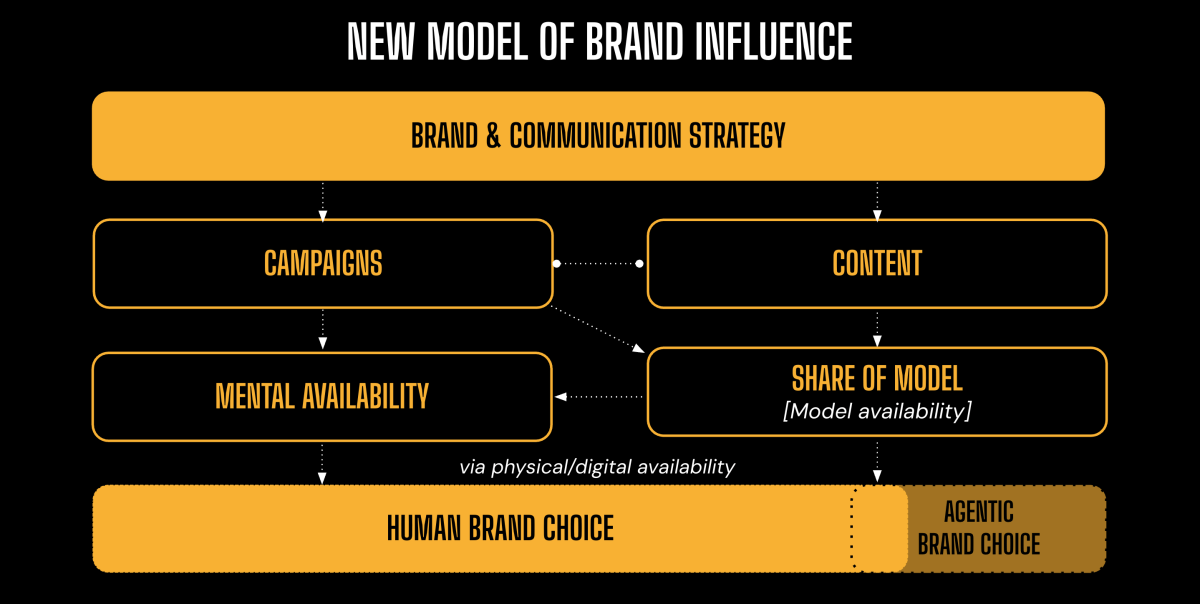

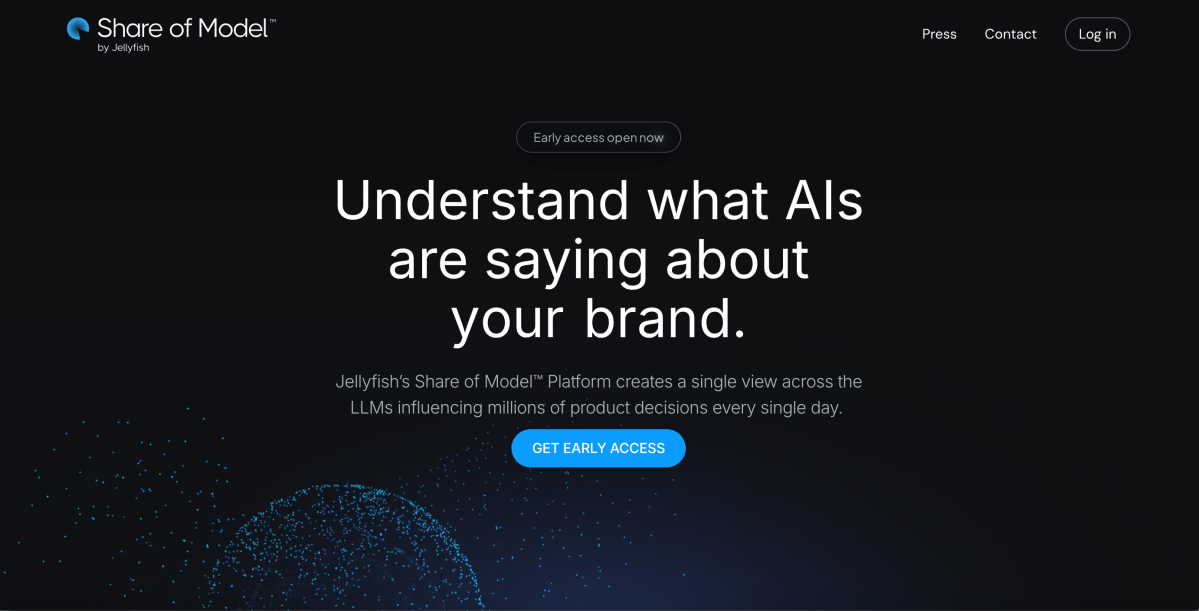

One of the most pioneering things we’ve done over the last couple of years is in helping clients to understand the visibility and perception of their brand in the LLMs. In 2023 we (specifically Jack Smyth) pioneered a completely new concept – share of model – and we built a platform of the same name to measure it. You can learn more about the platform here (https://shareofmodel.ai/). An exceptionally wide number of clients now use it across a range of use cases. I wrote about it in this (https://www.marketingweek.com/brand-building-ai-world/ ).

I also touched on this in an article from last year which is also proving to be a commonly requested talk by me (https://www.marketingweek.com/brand-building-ai-world/).

Writing this was a great way to get closer to my Jellyfish SEO/GEO colleagues who really are leading the industry in thinking about the transition from the world of SEO to the brave new world of GEO, and how brands can ensure they’re taking advantage of this shift to ensure their brand continues to be discoverable in this new environment.

This article also touches on some of the fascinating new questions that brands are asking us: how do you ensure your brand guidelines are still fit for purpose, how do you ensure your brand is showing up in the right way, and your communications strategies are fit for this new era. This is stuff you may not be getting from your SEO agency, your media agency, your creative agency, your content agency, your social agency, but we’re well placed to think about, with experts in all these areas.

Brand strategy

A frequent question I get is ‘what exactly do you and your brand strategists do at Jellyfish?’. It’s a fair question given the range of services Jellyfish offers, our history in the performance space, and the fact that we’re often working alongside other agencies whose primary role is as the brand and/or creative strategy agency.

We’re a small global team who work in a number of ways, which flexes from brand to brand, project to project. A lot of our time is spent pitching, especially for creative, social and production accounts. We’re useful for organic client growth, where on production-led accounts where the agency wants to be able to offer additional services we’re helping teams have more upstream client conversations. We often partner with our media strategy colleagues in offering support when a media account is looking for more upper funnel brand or creative strategy thinking, in helping spot creative opportunities and shaping creative briefs on media accounts.

Here’s what we say about ourselves in our job ads for brand strategists – it’s of course a somewhat idealised version of what strategy is here (but what do you expect from an ad?).

Jellyfish Brand Strategy builds brands at marketing’s cutting edge. The team applies timeless brand building principles to ground-breaking execution in today’s platforms. Brand strategists help connect Jellyfish’s wide set of capabilities and help join up our strategic and creative thinking. They help drive convergence, bridging creative and media, brand and performance, humans and AI. They help Jellyfish win new clients as well as service and grow existing ones.

Jellyfish brand strategists are naturally collaborative, often with a somewhat hybrid skillset, and love working alongside people in the wider Jellyfish strategy community – whether media or social strategists.

I’m aware how hugely lucky I am to be here and to have the platform I’ve got now with my Marketing Week articles, blogs, speaking engagements around the world, and other thought leadership opportunities.

If it wasn’t for my role at Jellyfish I wouldn’t have been able to observe close up what’s going on at the cutting edge of the industry and capture it in some of the big themes I’ve written and spoken about over the last 5 years – brand & performance; the performance plateau; fixing the sales funnel; Share of model; brand building in a world of creative fragmentation (aka Building Big from Lots of Littles with Dr Grace Kite); and most recently brand building in an AI world.

Anyway, hopefully you can see from all this that Jellyfish is a fascinating and unique place, that’s well set up to shape both the future of the brands we work with but also the future of the industry we’re in.

I love what I do and am very lucky to be given the opportunity to do it.

‘Brand’ in this world is far from being a static set of words in a strategy document. It’s a dynamic network that simultaneously builds and refreshes human memory structures while being constantly interpreted, reproduced and represented by machines.

‘Brand’ in this world is far from being a static set of words in a strategy document. It’s a dynamic network that simultaneously builds and refreshes human memory structures while being constantly interpreted, reproduced and represented by machines.

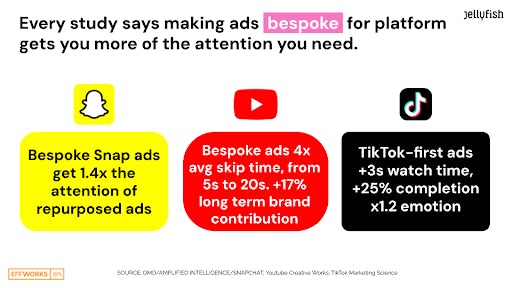

You need to be conscious of the limited, more fleeting attention many of these channels and ad formats usually get (as Karen Nelson-Field’s work warns), which could limit their ability to create or refresh the longer-lasting brand memories that can influence future sales. Attention measurement company Lumen recently introduced the concept of ‘aggregated attention’, which means thinking about the total amount of attention your campaigns are achieving.

You need to be conscious of the limited, more fleeting attention many of these channels and ad formats usually get (as Karen Nelson-Field’s work warns), which could limit their ability to create or refresh the longer-lasting brand memories that can influence future sales. Attention measurement company Lumen recently introduced the concept of ‘aggregated attention’, which means thinking about the total amount of attention your campaigns are achieving.

And it’s not a new issue for creative people to be wrestling with either. You can see it in the famous quotes of many of the ad legends of the 60s:

And it’s not a new issue for creative people to be wrestling with either. You can see it in the famous quotes of many of the ad legends of the 60s: